This post is in memory of Dick Giordano (20 July 1932–27 March 2010), original editor of Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

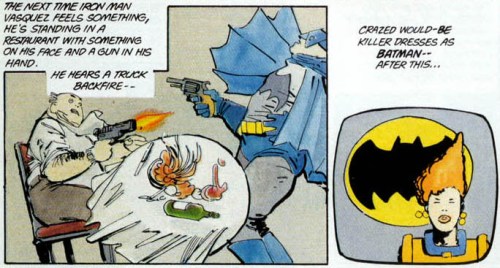

Time now to talk about Book Two (of four): “The Dark Knight Triumphant.” Having prevented Two-Face from destroying Gotham’s Twin Towers, Batman turns his attention to the Mutant gang that’s been terrorizing the city. We learn more about Commissioner Gordon’s impending mandatory retirement, and meet his successor: Captain Ellen Yindel, whose appointment (and hostility toward the Dark Knight) will motivate much of Book Three’s plot. Miller also introduces a new Robin, the young teenager Carrie Kelley, who will become a central character. And Superman is given subtle orders (by President Reagan) to help ensure that the newly-returned Batman stays in line.

The Grid

But first, I wanted to clarify some comments I made in my last post regarding the grid format of the entire miniseries. As I stated, each page is based on an underlying 4×4 grid. On some pages, Miller stages the action across the resulting sixteen panels. But on most pages, he “merges” two or more adjacent panels, creating a wide variety of unique compositions.

See, for instance, the following image, four consecutive pages from Book Two. I’ve drawn the 4×4 grid in black over the pages:

The Dark Knight Returns isn’t the only comic to use this kind of grid. Watchmen, also published in 1986, is composed on a 3×3 grid. And like Miller, Watchmen‘s artist, Dave Gibbons, regularly merged panels to vary the compositions:

Comparing TDKR and Watchmen proves instructive. Gibbons’s grid is much more evident throughout; Miller’s is looser. Miller’s panel merges are also more varied than Gibbons’s (while still respecting the underlying grid structure). The resulting images reflect well one of the dominant themes in TDKR: Batman’s struggles against anything or anyone that would cage him. Meanwhile, Gibbons’s more methodical, “within the lines” art is well-suited for the obsessive, clockwork-like precision of Watchmen.

By way of contrast, here are four adjacent pages from Uncanny X-Men #208 (August 1986):

No grid. Which isn’t a bad thing, per se. But Miller’s and Gibbon’s similar approach—their willingness to adopt a systematic constraint, and then explore within it various layouts and compositions—is one more element contributing to the artistry of their respective books.

The Mutants

Speaking of X-Men, Frank Miller pokes some fun at that comic by having Batman square off against “the Mutants.” (For anyone who doesn’t know, X-Men is about a team of mutant superheroes; due to a special “X-factor” in their DNA, they acquire strange powers during puberty. Stan Lee supposedly invented this device in order to save himself the trouble of having to create multiple origin stories for the characters.)

By 1986, Uncanny X-Men was one of the best-selling North American comics (something Batman’s book certainly wasn’t). A few panels of TDKR stand out as commentary on Marvel’s most popular title:

Batman: “We never faced anything like this… We fought only humans…”

The Mutant Leader, with his fangs and grotesquely disproportionate musculature, does look more like a character from the pages of X-Men:

In particular, his visor bears a certain resemblance to the one worn by the X-Men’s leader, Cyclops:

…and his bald head is reminiscent of the X-Men’s other leader, Professor Charles Xavier:

Stan Lee’s original title for The X-Men (later The Uncanny X-Men) was “The Merry Mutants.” (Imagine Bryan Singer trying to adapt a grim and gritty, post-TDKR version of that!)

Although he’s initially beaten by the Mutant Leader, by the end of Book Two Batman is able to outsmart and defeat the monster, causing the remaining Mutant gang members to transform themselves into “the Sons of the Batman”:

While still ostensibly a gang, this band of vigilantes now turns its rage toward “Gotham’s criminals”:

It’s telling, however, that this new gang’s rhetoric still echoes their former leader’s:

Miller’s own attitude toward vigilante justice is ambivalent. Although he clearly admires Batman, and what the character stands for and is capable of, he also takes care to present the Dark Knight as more than a little mentally disturbed. And Miller is repeatedly critical toward those who, inspired by the Dark Knight, adopt Batman’s methods:

Miller spoke directly about this contradiction in a 1985 interview with the Comics Journal:

I think that in order for [Batman] to work, he has to be a force that in certain ways is beyond good and evil. It can’t be judged by the terms we would use to describe something a man would do because we can’t think of him as a man. […] [I]t’s very clear to me that our society is committing suicide by lack of a force like that. A lack of being able to deal with the problems that are making everything we’ve got crumble to pieces. As far as being fascist, my feeling is … only if he assumed political office. [Laughter.] If there were a bunch of these guys running around and beating up criminals, we’d have a serious problem. (Thompson 34)

Miller’s reference to Nietzsche (“beyond good and evil”) seems deliberate. Later in the interview he states:

Batman, in my series, does not apologize or question what he does or its effects. There’s a whole world out there who can argue about that, and they do, constantly, throughout the series. And the effects of what he does are tremendous. He changes the quality of life in Gotham City, the way everyone there thinks and lives. Now, presenting a vigilante as such a powerful, positive force is bound to draw some flak, but it’s the force I’m concerned with, more as a symbol of the reaction that I hope is waiting in us, the will to overcome our moral impotence and fight, if only in our own emotions, the moral deterioration of our society. Not just some guy who puts on a cape and fights crime. That’s a great thing about superheroes, the substance of what makes them “larger than life.” Not that they can fly or eat planets, but that they can, or should, manifest the qualities that make it possible for us to struggle through day-to-day life. (Thompson 35)

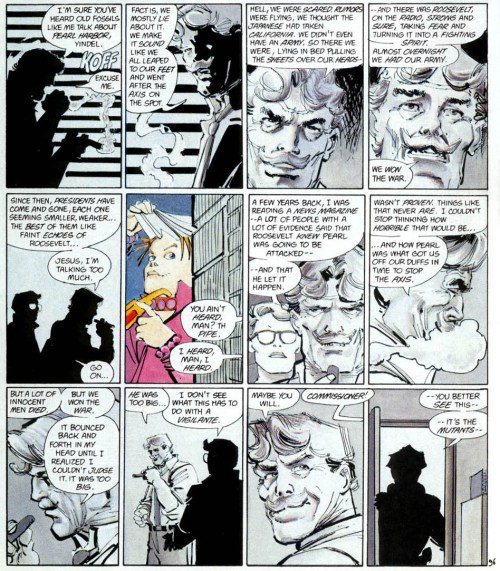

Miller locates this argument initially with Commissioner Gordon, who echoes the author in his advice to incoming Commissioner Yindel:

It’s important to remember that Miller views comics as fantasies—”romances” or “adventure stories” for adults:

I want it to be as thrilling as possible; I’m doing everything I can. But I don’t believe that adventure is simply child-like. I believe, from my own experience, that adventure is made up of real life, and that writing romantically—which is what I do, I use the term “romance” in its original meaning, as in Robin Hood and Captain Blood and Gone with the Wind—is using real emotions and conflicts, making them as clear and as strong as I can. In a way, my Batman is written more for an older audience than a younger one, because it has to do with things that I feel today, as a 28-year-old man. (Thompson 40)

Robin

It’s also telling that the gang formed in the wake of the Mutant Leader’s defeat is the Sons of the Batman. In opposition to them stands Batman’s true follower, the female Robin. Regarding the character, Miller wrote in his introduction to TDKR‘s 10th Anniversary Edition (1996):

I’d never intended to use Robin. But then, one day, I pictured a little bundle of bright colors leaping over buildings, dwarfed by a gray-and-black giant…and there she was. Robin.

Not that my version sprang into my head full-blown.

1985. At 30,000 feet. I talk to cartoonist John Byrne about Batman. John talks to me about Robin. “Robin must be a girl,” he says. He mentions a drawing by Love & Rockets artist Jaime Hernandez of a female Robin. To prove his point, John provides me with a pencil sketch of his own.

I would argue that this Robin, Carrie Kelley, is the most wholly sympathetic character in TDKR. Not unlike the Sons of the Batman, Carrie, inspired by Batman’s struggle, chooses to follow him. And after sewing her own Robin costume and playing pranks on a few petty criminals, she wins her hero’s respect when she saves him from death at the hands of the Mutant Leader:

She wills herself into becoming Batman’s sidekick. Yet, unlike so many of the other characters in TDKR, she remains relatively nonviolent. As we see in the above panels, she’s a healer, and her chosen weapons are nonlethal children’s toys like firecrackers and a slingshot:

Carrie is the only major character in TDKR who doesn’t kill anyone—and it’s worth noting that this thirteen-year-old character is introduced in Book Two immediately after Commissioner Gordon fatally shoots a would-be assassin, a member of the Mutant gang “who isn’t yet old enough to shave” (58). Furthermore, when happenstance saves Carrie from death at the hands of the Joker’s sidekick (who himself then dies), her immediate reaction is to cry:

Interestingly, Carrie Kelley bears a strong visual resemblance to the miniseries’ other major female character, Captain/Commissioner Ellen Yindel:

There will be some payoff for this in Books Three and Four. (And, no, the two characters aren’t related!)

The Dark Knight Returns

In my analysis of Book One, I pointed out some of the thematic ends to which Miller turned the comic panels themselves. That work continues in Book Two. Batman’s first appearance in this second book, for instance, involves a giant bat once again crashing through a window:

This time, the bat (presumably) flies out—but a batarang flies in.

Later, in the Batcave, Miller echoes Book One by having Bruce Wayne become obscured by the wing of an advancing bat:

(This kind of repetition is facilitated by the underlying grid structure.)

And Book Two ends with another direct reference back to Book One, where the image of a bat crossing the moon triggered Bruce Wayne’s nightmare, resulting in his eventual relapse into Batman:

This time, the sequential images of the bat are interrupted by images of Bruce Wayne standing at the window. He is fully bound up within that bat’s flight. Once again, the window panes—which are also comics panels—are presented as crosses, again laid directly over Bruce Wayne’s face and upper body. The reading is obvious: his life as Batman, as a comic book superhero, is inescapable, his eternal cross to bear. Bruce Wayne can be only temporarily restrained by those panels/windows/cages—given time, the bat will always crash through, releasing Batman.

Misc.

Finally, here are a few random observations I wanted to make about Book Two.

1. Miller works in a reverse reference to his own miniseries Ronin (1983–4). You’ll recall that Book Four of Ronin features a scene in which one of the protagonists, Casey, is overcome by a band of Morlock-like creatures:

This time around, Miller begins in darkness, then takes the fingers away:

2. On page 83, a television announcer mentions a porn star named “Hot Gates.” This is of course a reference to Thermopylae, where in 480 BCE the Spartans and their allies delayed the invading Persian army of Xerxes I—a story Miller later told (in his own idiosyncratic fashion) in his 1998 miniseries 300.

3. I’ll write more later about TDKR‘s impact on the comics industry (and elsewhere), but until then, here’s a bit of Dark Knight homage: an episode of Paul Dini’s The New Batman Adventures, “Legends of the Dark Knight” (1998). Its plot is a condensation of some of Book Two:

Until next time, happy reading (and viewing)!

I don’t know if I’ve said so before, but these posts are absolutely amazing. This was one of my first great comic loves, and it’s so awesome to read about it at this level. Thank you.

I’m really enjoying these. Just read TDKR for the first time a couple of weeks ago, and it keeps sneaking back into my head… This is a really excellent series of posts.