Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

Monday was David Letterman‘s birthday, making this an okey-dokey time to talk about Book Three of The Dark Knight Returns, “Hunt the Dark Knight”…

Let’s plunge right into it!

Broadening Narration

So far I’ve been focusing on The Dark Knight Return‘s more innovative aspects, but one shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that it’s still a superhero comic. Indeed, it’s to Miller and company’s credit that one can “simply” enjoy the miniseries as a very satisfying superhero story (which is how I first encountered it, as a kid). Miller’s take on Batman was simultaneously very familiar and yet unlike other American comics up to that point, which is part of its great artistic accomplishment: like Watchmen, it’s rigorous and experimental, expanding comics’ potential—and yet it’s also very approachable and enjoyable (it was a commercial bestseller).

One way that TDKR remains a conventional superhero comic is that each book features a guest villain. Miller integrates this so organically into his larger narrative that it’s possible to miss that each one of its four parts culminates in fisticuffs against a different foe. Book One sees Bruce Wayne’s return to the role of Batman, which leads to a confrontation with the similarly-returned super-villain Two-Face. Book Two sees Batman respond to crime on a larger, more “contemporary” scale, defeating the Mutant gang. Now, in Book Three, the Joker subplot from the first two chapters reaches its own violent climax. (Book Four will see its own final battle.)

But why, then, doesn’t TDKR just read as four times the same battle? What, besides its impressive production design, occasional metatextual commentary, and running visual motifs, distinguishes it from other comics that were on the rack at the time? What makes it a graphic novel, and not just a four-part serial narrative?

Part of the answer lies in how the entire project develops from issue to issue. Miller employs an omniscient POV throughout the miniseries, but the nature of that narrative perspective changes between Books One and Four—it systematically expands or unfolds, revealing a broader structure. What’s more, the changes in how the story is told mirror the overall contents of the story—which is fairly sophisticated for “a superhero comic.”

Book One is tightly harnessed to Bruce Wayne/Batman. He appears on 36 of its 47 pages, and in roughly 505 of its 742 panels. (Due to the grid-based nature of the art, each page has 16 panels—or potential panels—which makes 16 x 47 pages = 742 panels/book.) Furthermore, he is discussed on nearly every single page. He is the only character who addresses the reader directly, and we are privy to one of his dreams as well as his memory of his parents’ murder. The major supporting characters Commissioner Gordon, Carrie Kelly (Robin), and the Joker are all introduced by page 22, but they take up very little space for the time being (very few panels), and we don’t know what any of them are thinking.

Initially, Bruce Wayne’s thoughts are placed above panels he’s in…

…but once he resumes his Batman identity, he begins thinking in gray word balloons (well, boxes):

Interestingly, there’s a moment early on in Book One where Wayne is confronted by two Mutant gang members in Crime Alley (the spot where his parents were murdered). For a moment, his thinking shifts into gray boxes—foreshadowing his relapse into Batman:

This is a great example of how thoroughly Frank Miller has thought through his project. (It’s also a good example of a narrative potential unique to comics.) People often criticize Miller’s work for being broad and bombastic—and to be fair his later comics often (deliberately) are—but TDKR demonstrates just how subtly masterful his work can be.

But let’s return to the overall structure of the series. Batman, as it turns out, isn’t the only narrator of TDKR. Beginning with Book Two, he recedes somewhat, even as he remains the focus of every other character’s attention. (Here, he appears in roughly 428 panels, almost 100 fewer than in the first book.) Book Two opens with Commissioner Gordon addressing the reader, and for the rest of the series we have access to his thoughts. Like Bruce Wayne’s in Book One, they appear above the panels he’s in:

(This will change somewhat in Book Four, but more about that in the next post.)

We also gain access to Carrie Kelly’s thoughts—but only after she puts on her homemade Robin costume. (In other words, donning a costume—choosing to become a superhero—gives her a voice in the story.) Her thought boxes are yellow:

Book Three opens the story up even further, and Batman becomes even less central. Here, he appears in about 416 panels, down 12 from the previous chapter. (That’s not much, but it continues the trend—and we’ll see a rather large decline in Book Four.)

Book Three, just like Book Two, adds two narrators. Book Two began with what Commissioner Gordon was thinking, and now we start inside Superman’s head, showing us things from his point of view as he hurtles toward Gotham City:

The other new narrator, a bit later on, is the Joker, who in this chapter finally comes into his own. Miller presents his thoughts in green (see, for instance, the image at the top of this post).

This increase in narrators, and Batman’s diminishing role as the central character, is naturally accompanied by the story’s increasing complexity. “Hunt the Dark Knight” presents multiple simultaneous plotlines: Batman and Robin investigate the Joker’s developing plot; Superman struggles against USSR-backed forces in the (fictional) South American country Corto Maltese; and the Joker prepares for his appearance on “The David Endochrine Show.” Meanwhile, the TV media continues its role of Greek chorus, a series of now-familiar TV screens that pepper the text, providing transitions and exposition, as well as filling in little details of what’s happening elsewhere in Gotham City.

Correspondingly, Book Three sees more of the outside world pressing inward. Besides Superman’s appearance and the escalating military situation in Corto Maltese, Miller caricatures more celebrities: David Letterman, Dr. Ruth, Ronald Reagan. We also learn (from Superman’s thoughts) more of TDKR‘s backstory: why Batman retired, and what happened after that. In a plotline similar to Watchmen (which was published the same year), there was some kind of crackdown on costumed superheroes:

Bruce Wayne retired, Diana (Wonder Woman) “went back to her people,” Hal (Green Lantern) “went to the stars” (120). Oliver (Green Arrow) was incarcerated and eventually became a fugitive (139). (He’ll turn up in Book Four.) And now, by returning, Batman has become a fugitive as well. (Commissioner Yindel’s warrant for his arrest is echoed by Superman’s threats.)

Superman alone has continued on as a superhero, and Miller paints an unflattering portrait of the Man of Steel. While working on TDKR Miller told the Comics Journal:

One of the main problems with Batman as he has been treated is that in DC Comics, like Marvel Comics, the ridiculous number of superheroes creates a sense of a very benevolent universe. There are lots of good guys, and they win each time. Superman alone, since they made him able to fly through suns and survive nuclear explosions, implies that the world’s okay, that he’s powerful enough to protect all of us. But Batman only works if the world really sucks. I split the kids who get into Superman and the kids who get into Batman into two groups. Kids with a sort of happy, benevolent view of the world tend to go toward Superman, and kids who find the world a big, scary place go for Batman. (Thompson 36)

This contrast between the characters is established clearly in their second meeting:

Superman then turns around, missing the fact that the natural world is not only beautiful, but vicious:

Miller is quick to point out the cost of Superman’s continued role as a costumed do-gooder: he’s called away by Reagan, and sent to intervene in the battle in Corto Maltese between US and Soviet Forces. He calls what he’s doing there “saving lives,” but it looks to me as though he’s little more than Reagan’s enforcer—a one-man branch of the US military. In exchange for a “license” and his life, Superman is required to remain quiet, invisible, and above all obedient:

Here and elsewhere we see that there’s a media blackout on mentioning Superman: news anchor Lola Chong is warned whenever she hints that he might be in Gotham (109, 111). Accordingly, when Superman does show up in Gotham (at the start of the book), he keeps out of sight: Miller depicts him as a shaft of blue light, or as moving too quickly to be seen.

In both of these two meetings, the reader’s refused (for now) the sight of Batman and Superman “onscreen” together (both in their iconic costumes, battling crime). That said, Miller does work in one homage to the characters’ shared past: Superman arrives as Batman is fighting a neo-Nazi—a sly wink to their 1940s adventures:

(See this article for more on superhero comics during WWII.)

The Batsuit

The first seven pages of “Hunt the Dark Knight,” besides seeing Superman’s arrival, find Batman wearing a curious outfit:

As has often been noted, Batman is unique among costumed superheroes in that he possesses no super-powers. He is instead the ultimate tool user. His costume includes a utility belt, and it’s worth taking a moment to recall the precise meaning of that word: “to put to use; turn to profitable account.” Batman’s chief strength is his mastery over tools: he’s the most accessorized superhero, spending his fortune on dozens of weapons, vehicles, and gadgets…

He puts things to use; he turns what’s at hand to profitable account. (Later in Book Three he once again dons a different identity, impersonating a police lieutenant to gain some crucial information.) Indeed, it’s a running joke in the DC Universe that Batman could defeat any other character, even Superman, if given enough time to prepare. (Miller will explore this idea himself in Book Four).

Batman’s costume actually changes steadily throughout TDKR. Books One and Two see him wearing his familiar blue-and-gray outfit, based on Neal Adams’ 70s/80s Batman costume:

But in Book Two, after Batman’s initial defeat at the hands of the Mutant leader, Miller switches to a darker, more compact design:

Miller removes the suit’s bright yellow sections and the long ears, arguably making the costume more practical for urban crimefighting. (To the best of my knowledge, this is the source of our contemporary view of Batman as an urban warrior.) Meanwhile, Miller’s redesign recalls the original black-and-gray Batman costume:

There will be one more costume change to come, in Book Four.

Incidentally—if you’ll allow me an aside—one disappointment of the Batman movies (beyond the fact that they’re generally terrible) is that they consistently screw up Batman’s costume, dressing him in something that looks simply hideous. The only live-action adaptations that have gotten the costume anywhere close to right are the 1960s TV show (which at least looks like Batman and like real clothing) and the ridiculously goofy fan-film “Batman: Dead End”:

End of aside.

The American Flag as Costume

Let’s return to the dirty costume that Batman’s wearing at the start of Book Three. Two things stand out here. First, Miller’s created a visual rhyme with the end of Book Two, which saw Batman covered in mud (which he used as a tool, enabling him to defeat the Mutant leader):

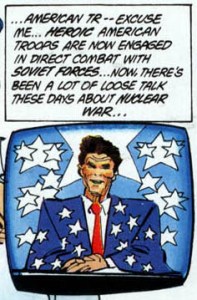

But what interests me more here is the US flag scarf that Batman is wearing. Book Three, in contrast to all of the other books, has US flags everywhere. The image runs throughout the issue, and always as part of someone’s clothing. The next one is being worn by Ronald Reagan:

Next, the Joker-controlled Congressman Noches wears one—briefly:

And when Batman and Robin find Selina Kyle (after she’s been attacked by the Joker), she’s dressed up in a Wonder Woman costume:

In the midst of all this, Superman can be read (like his master Reagan) as a giant walking US flag, as Miller definitively establishes in Book Two:

All of these flags reflect Book Three’s growing political awareness, broadening its portrait beyond Gotham City to take in Reagan’s anti-Communist realpolitik. Beyond that, I so far don’t see a clearer interpretation. Reagan’s flag-suit seems a self-serving political image, but the other uses are more ambiguous, more ironic—they undercut its authority. And why does the Joker bother to dress Selina Kyle in Wonder Woman’s costume? (Why not a Catwoman costume?)

I’ll try to return to this issue in Part 6. In the meantime, there’s still one more flag to go, which we’ll get to in a moment.

The Joker

Book Three sees Batman catch up with the Joker, who, after murdering everyone in attendance at “The David Endochrine Show,” has fled to the County Fair, where he is randomly killing people. Batman vows to put an end to his arch-nemesis (an oft-heard comics refrain—see, for instance, Batman: Dead End above).

Batman’s battle with the Joker rages throughout the fair, at one point passing through a hall of mirrors, evoking Orson Welles’s 1947 noir The Lady from Shanghai (see starting two minutes in, onward):

Once again, Batman’s arrival is heralded by a bat crashing through glass:

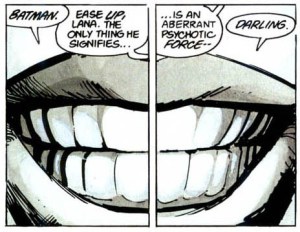

But their fight ends, appropriately, in the Tunnel of Love. And we’ll recall that the first two words out of the Joker’s mouth, after seeing a report of Batman on TV and recovering from his catatonic state, were:

The Joker repeats himself upon Batman’s arrival:

By the book’s end, Batman has defeated the Joker, but only after being shot and stabbed. And the Joker, whom Batman paralyzed, manages to then kill himself, his final revenge being to frame Batman as his murderer. As we saw in Books One and Two, the final panel pulls together many of this chapter’s threads:

The Joker and Batman slump together, lovers reunited. And there, in Batman’s red wound and the Joker’s white face and blue shirt, lies our final American flag.

Next: “The Dark Knight Falls”!

Once again, this has been pretty amazing to spend time with.

Great analysis, I’m thoroughly enjoying the series.

I don’t know if Miller’s ever addressed it, but I always thought an interesting interpretation of the Joker’s death is that Batman actually DID kill him. There’s little doubt that we’re getting the book from his perspective, and considering how much of his psyche is getting exposed on the page, maybe he just blocked out what was ultimately necessary, and we see how HE sees it.

Yes, “Batman doesn’t kill” – and no one knows that better than him, which is why he might not be able to accept it.

I’m not saying that’s the absolute truth of the scene. There’s an intriguing ambiguity in the presentation – the two of them are alone, we get Batman’s bias – that I enjoy, and it makes me reflect on the work even more.

Frank miller is the man. Luv two of hes book the dark knight return n the dark knight falls.is a classic back in the 80s batman is old but he could kick ass the two parts r good never read 3 n 4 of the parts of batman is a good comic book