1987’s Mannequin is a film about the transformative potential of aesthetics. Specifically, window dressing. The film’s main characters are employed as window dressers. So too are they window dressing, both literally — the titular mannequin is used to decorate store windows — and figuratively, as their characterizations do not aim for psychological complexity. The film’s own aesthetic values surfaces over what some might consider “substance,” as evidenced by its abundance of escapist dance and fashion montages, which have little utility to the film’s plot, but from which I draw considerable pleasure:

The film’s greatest fantasy may not be that a mannequin comes to life (as fantasies go, relatively mundane), but rather the gravity with which the film imbues the profession of window dressing. Indeed, the film’s plot pivots on the power of a fabulous window display to determine the fortunes of retail corporations, as well as the creative fulfillment and self actualization of its protagonist.

(Can you imagine anything faggier?)

Protagonist Jonathan Switcher (last name sounds kinky, no?) gets directly implicated in “otherness” when his fellow window dresser, the flamboyantly gay Hollywood Montrose, discovers his amorous attention to the mannequin and suggests Switcher’s even “weirder” than himself. The film’s “good guys” unite as Queer coalition against the Man. Led by a fearless matriarch played by Queer icon Estelle Getty, the employees of Prince and Company battle the heteropatriarchal machinations of rival department store Illustra, including a homophobic security guard, a sexually-harassing douchebag CEO and James Spader as the kind of slimeball one imagines stores women’s corpses in his freezer.

Sure, Hollywood Montrose is troublingly buffoonish, tragically pathetic. A black fag who exists solely to further the white straight boy’s dramatic action. Who isn’t even successful as a window dresser, who must ask said white boy for help when his dressing outshine his own. But consider: Maybe he hasn’t shown us all his cards, for the sake of survival, is biding his time, is covertly the fiercest emissary of fierce. Behind his formidable sunglasses hide cyclops eyes with the power to vanguish fuckheads. Ultimately, his traumas are no joke, and those who value his distinctiveness will collectively apply a salve. At home, in the privacy of his bedroom, with his lover, his Queenly screams are a song. And man can he work a hose:

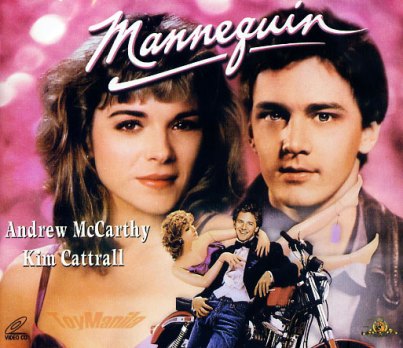

And what about mannequin Emmy? As Switcher’s muse, isn’t she a classic patriarchal trope? (Kim Catrall’s performance recalls for me Olivia Newton John in Xanadu, another camp classic that, though significantly more ambitious and less c0mmercially successful, was similarly reviled by critics). And yet: The film begins with, is enabled by, Emmy’s act of agency, her refusal to accommodate the strictures of her time. And don’t we imagine she has more in mind for her embodied future than to live as Switcher’s sex toy? Emmy simultaneously promises and withholds what for many represents a significant fantasy within patriarchy — the ability to control her own status as object, to switch at will from person to thing. Unfortunately, ultimately, she can only become human under her male lover’s gaze, and it’s said lover’s name — Switcher — that signifies the radical action we wish she could fully claim for herself.

Enjoying Mannequin’s spectacle, I’m left wondering what differentiates its trash culture from a more “legitimate” work of art that embraces a camp aesthetic — for instance, something like the Derek McCormack text that so delighted me last week? One thing that comes immediately to mind is: while McCormack elevates language, accomplishing things through text that can only be accomplished through text, Mannequin is formula movie-making, does nothing to elevate cinema as a form. And the camp sensibility that might embrace a film like Mannequin, and consider with grave earnestness its frivolity, is perhaps only possible, as Sontag tells us, retroactively, after the passage of time.

In its time, Mannequin received but one honor — an Oscar nom for its theme song “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Now,” with vocal from the great fallen rock icon Grace Slick, whose much-maligned Starship also recorded “We Built this City,” the song Dominating Penis Music Review Blender once called the worst single of all time. As I imagine myself joining hands with Hollywood Montrose and Emmy the mannequin to kick some unfabulous ass, I’ma sing its chorus (join me!):

And we can build this dream together

Standing strong forever

Nothing’s gonna stop us now.

I enjoyed this post! Who knew there was so much to say about this movie? I look forward to its next showing on TMC, and also having an opportunity to use my new favorite mantra, “Can you imagine anything faggier?” in polite conversation at an upcoming dinner party. Thanks!

Refreshingly astute! Your observations of culture, subculture, and the psycho-social emergence of supporting cast as revolutionary icons renew my faith in modern storytelling. Translation: I dig the way you unearth socially redeeming value where it is seemingly nonexistent!