“…the iniquity of oblivion blindely scattereth her poppy, and deals with the memory of men without distinction to merit of perpetuity.” – Urne-Buriall, page 84

Sir Thomas Browne wrote Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall or, A Brief Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes Lately Found in Norfolk in 1658. Just a few months ago New Directions reprinted the book with opening remarks by W.G. Sebald from his chapter on Browne in The Rings of Saturn.

The discourse is brief but other worldly. As Sebald says, it’s a “part-archeological, part-metaphysical treatise,” with the first three chapters presenting the urns and their contents, how world cultures have buried their dead, as well as references to Homer, the ancient philosophers and scientists and Dante. The last two chapters are more speculative–extended flights of fancy, meditations on existence, death and the possibility of worlds beyond ours.

If we begin to die when we live, and long life be but a prolongation of death; our life is a sad composition; We live with death, and die not in a moment. (80)

And therefore restless inquietude for the diuturnity of our memories unto present considerations, seems a vanity almost out of date, and superanuated peece of folly. We cannot hope to live so long in our names, as some have done in their persons, one face of Janus holds no proportion unto the other. ‘Tis too late to be ambitious. (82)

The treasure of this Baroque style (or ‘Ornate style’ as George Saintsbury refers to it in his A History of English Prose Rhythm from 1912, where he says the fifth chapter of Urne-Buriall is the “the longest piece, perhaps, of absolutely sublime rhetoric to be found in the prose literature of the world”) is the language and the antique spellings of the words. There is no screen between the reader and the 17th Century, it is as close as one can get to a time full tremendous wars, plagues and scientific revolution. The meditations on death are something especially striking to me because it seems we live in a time now when death is so covered up, where pictures of caskets are banned, where deaths take place impersonally in hospitals and not at home and where popular media inundates the air waves with life-prolonging schemes and drugs.

I was very happy to spend the last three mornings with a man who kept posing questions only to say he didn’t know the answer. When recording devices are aimed to capture every conceivable angle I often wonder what happened to the mystery of being? The mystical? I know it still exists as I know death does, albeit through a glass, darkly.

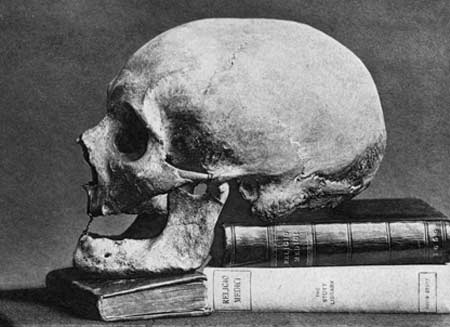

Browne is a treasure. Is it no surprise he died on his birthday and his bones were dug up and displayed in a bell jar two-hundred some years after his death (photo above), only to be buried once again?