“…the iniquity of oblivion blindely scattereth her poppy, and deals with the memory of men without distinction to merit of perpetuity.” – Urne-Buriall, page 84

Sir Thomas Browne wrote Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall or, A Brief Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes Lately Found in Norfolk in 1658. Just a few months ago New Directions reprinted the book with opening remarks by W.G. Sebald from his chapter on Browne in The Rings of Saturn.

The discourse is brief but other worldly. As Sebald says, it’s a “part-archeological, part-metaphysical treatise,” with the first three chapters presenting the urns and their contents, how world cultures have buried their dead, as well as references to Homer, the ancient philosophers and scientists and Dante. The last two chapters are more speculative–extended flights of fancy, meditations on existence, death and the possibility of worlds beyond ours.

If we begin to die when we live, and long life be but a prolongation of death; our life is a sad composition; We live with death, and die not in a moment. (80)

And therefore restless inquietude for the diuturnity of our memories unto present considerations, seems a vanity almost out of date, and superanuated peece of folly. We cannot hope to live so long in our names, as some have done in their persons, one face of Janus holds no proportion unto the other. ‘Tis too late to be ambitious. (82)

The treasure of this Baroque style (or ‘Ornate style’ as George Saintsbury refers to it in his A History of English Prose Rhythm from 1912, where he says the fifth chapter of Urne-Buriall is the “the longest piece, perhaps, of absolutely sublime rhetoric to be found in the prose literature of the world”) is the language and the antique spellings of the words. There is no screen between the reader and the 17th Century, it is as close as one can get to a time full tremendous wars, plagues and scientific revolution. The meditations on death are something especially striking to me because it seems we live in a time now when death is so covered up, where pictures of caskets are banned, where deaths take place impersonally in hospitals and not at home and where popular media inundates the air waves with life-prolonging schemes and drugs.

I was very happy to spend the last three mornings with a man who kept posing questions only to say he didn’t know the answer. When recording devices are aimed to capture every conceivable angle I often wonder what happened to the mystery of being? The mystical? I know it still exists as I know death does, albeit through a glass, darkly.

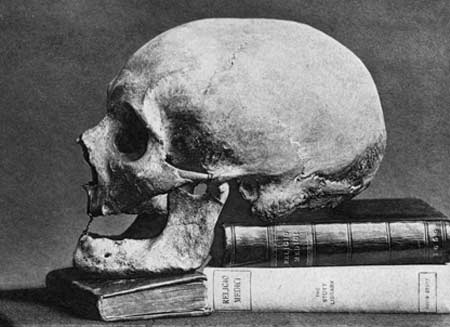

Browne is a treasure. Is it no surprise he died on his birthday and his bones were dug up and displayed in a bell jar two-hundred some years after his death (photo above), only to be buried once again?

Greg, as I noted elsewhere, I’d compliment you for the fine post except that for Browne, compliments were dross & worse — anathema.

Still, since my own skull’s still covered w/ skin & (mostly) hair, I doff my cap.

A nice appreciation! Worth remembering that ‘Urn-Burial’ is only one half of Browne’s 1658 diptych discourses. In complete contradistinction to the themes and imagery of ‘Urn’, ‘Cyrus’ concerns itself with light, growth, science and the future. Browne even ‘predicted’ his death to occur on his birthday.

Thank you Kevin. Your site is very Browne and informative. I hope to get to ‘Cyrus’ soon. So much to read.

Love this. I will have to check out Browne now. Sounds wonderful. I just picked up Rings of Saturn and In Ruins, so perfect companion to those two.

While there’s a certain solemnity and melancholy to Hydriotaphia or Urne-Buriall, it rarely, if ever, sinks to despondency. And while a certainty of life’s brevity pervades the text, Browne almost considers it beyond the point:

Beside, to preserve the living, and make the dead to live, to keep men out of their Urnes, and discourse of humane fragments in them, is not impertinent unto our profession; whose study is life and death, who daily behold examples of mortality, and of all men least need artificial memento’s, or coffins by our bed side, to minde us of our graves.

I think Browne may have been trying to distance himself from critique that his interest in the urns was simply morbid curiosity, because he later seemingly contradicts the quoted passage above by going on to describe how important his study of the urns will surely prove itself to be:

‘Tis opportune to look upon old times, and contemplate our Forefathers. Great examples grow thin, and to be fetched from the passed world. Simplicity flies away, and iniquity comes at long strides upon us. We have enough to do to make up our selves from present and passed times, and the whole stage of things scarce serveth for our instruction.

That final sentence resonates for me as a kind of proto-ontological statement. I’ve been thinking a lot, lately, about how we make our selves up, that we’re, at best, an unstable assemblage of past and present—hardly a new idea. Contrary to Browne, though, in my better moments I feel like the “the whole stage of things” is abundant rather than scarce, and it is that abundance that is daunting and harrowing, as well as wonderful and possibly even fulfilling.

In the last paragraph of the fourth chapter, Browne offers this possible blow:

“It is the heaviest stone that melancholy can throw at a man, to tell him he is at the end of his nature; or that there is no further state to come, unto which this seemes progressionall, and otherwise made in vaine…”

It seems to me that Browne offers little to assuage the blow of melancholy’s stone, instead offering that “the superior ingredient and obscured part of ourselves” (whatever that might be isn’t defined) might “tell us we are more then [sic] our present selves…”

The justly famous final chapter is filled with all kinds of wonderful reflections on life (“Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible Sun within us.”), death, uncertainty, fate, fame, time (“There is no antidote against the Opium of time, which temporally considereth all things…), and eternity. Here’s another of my favorites: “But the most tedious being is that which can unwish it self, content to be nothing, or never to have been, which was beyond the male-content of Job, who cursed not the day of his life, but his Nativity…”

Gass raves about Browne’s prose throughout his essays, and Hydriotaphia or Urne-Buriall is one of his “pillars.” In A Temple of Texts, he calls Browne “Sir Style”:

Sir Style is a skeptic; Sir Style is a stroller; Sir Style takes his time; Sir Style broods, no hen more overworked than he; Sir Style makes literary periods as normal folk make water; Sir Style ascends language as if it were a staircase of nouns; Sir Style would do a whole lot better than this.

I would guess that why so many of the literary titans admire him so is he did it differently. He had his subjects, his concerns and without character or melodrama he created structures that move us. As Woolf says:

“Then while most fiction, the nine volumes of M. Proust for example, makes us more aware of ourselves as individuals, Urn Burial is a temple which we can only enter by leaving our muddy boots on the threshold. Here it is all a question not of you and me, or him and her, but of human fate and death, of the immensity of the past, of the strangeness which surrounds us on every side. Here, as in no other English prose except the Bible the reader is not left to read alone in his armchair but is made one of a congregation.”

He comes to look at the urns and says aloud, “What does this mean? And what does it mean in the face of everything that has happened on earth?” His answer is no answer, but a translation of his brooding, a brooding that soars.

The last chapter reminds me of how Tarkovsky ended MIRROR – another assembly type work with no ‘plot’ but full of impressions and memories. The film director’s mother is remembered and his grandmother walks himself and sister through an Elysium-type setting as Bach’s St. Johannes Passion swells. It’s a triumph that art can shrug off “endings” and create music and image that is it’s own reckoning. Pater’s Conclusion to The Renaissance where echoes of Browne abound as he says:

“every moment some form grows perfect in hand or face; some tone on the hills or the sea is choicer than the rest; some mood of passion or insight or intellectual excitement is irresistibly real and attractive for us, – for that moment only” – “To burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.”

Anyway, Tarkovsky:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GC9ciRNW6DU&feature=related]

I’m reading the Saintsbury, now, on Hydriotaphia or Urne-Buriall; and he calls its final chapter “an unbroken and, at most, spaced and rested symphony.”

Of the Browne, Milton, and Taylor triumvirate, Saintsbury calls Browne “the greatest of the three—if not in all ways, yet certainly in those which we are more specially treading,” that is, in terms of rhythm and balance, and that his “greatness is indeed rather in the sentence than in the paragraph, though he has paragraphs of unsurpassed architecture…”

Oh, to compose sentential symphonies, to build paragraphic cathedrals!

As per our prior discussion: England had a civil war in the middle of the century and in 1649 they killed the king. Both these events are hard to comprehend for people in our time (or so I think) but Milton and Browne were there, soaking it up.

Virginia Woolf’s thoughts on Urne-Buriall (found in her essay “Sir Thomas Browne”, a review of the Golden Cockerel edition of the Works of Sir Thomas Browne, (1923)) are worth reading. Here, after reveling in Browne’s virtuosic prose, she then warns about the pitfalls of technical examinations:

A bold and prodigious appetite for the drums and tramplings of language is balanced by the most exquisite sense of mysterious affinities between ghosts and roses. But these dissections are futile enough, and indeed by drawing attention to the technical side of Sir Thomas’s art do him some disservice. In books as in people, graces and charms are delightful for the moment but become insipid unless they are felt to be part of some general energy or quality of character. To grasp that is to know them well, but to dally with charms and graces, to appraise them more and more exquisitely, is to be always at the first stage of acquaintance, superficial, polite, and ultimately bored. It is easy to detach the fine passages from their context, but in Urn Burial this character, this quality of the whole, though it expresses itself with all the charm of all the Muses, is yet of a very exalted kind. It is a difficult book to read, it is a book not always to be read with pleasure, and those who get most from it are the well-born souls.

Of those so-called well-born souls she also says: “Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne, but those who do are of the salt of the Earth.”

I can’t resist quoting more of Woolf’s appreciative lines, the composition of which are as virtuosic as the lines she praises:

For the imagination which has gone such strange journeys among the dead is still exalted when it swings its lantern over the obscurities of the soul. He is in the dark to all the world; he has longed for death; there is a hell within him; who knows whether we may not be asleep in this world, and the conceits of life be but dreams? Steeped in such glooms, his imagination falls with a peculiar tenderness upon the common facts of human life. He turns it gradually upon the flowers and insects and grasses at his feet, so as to disturb nothing in the mysterious processes of their existence. There is a halo of wonder round everything that he sees. He that considers the thicket in the head of a teazle “in the house of the solitary maggot may find the Seraglio of Solomon”. The tavern music, the Ave Mary bell, the broken urn that the workman has dug out of the field plunge him into the depths of wonder and lead him, as he stands fixed in amazement, to extraordinary flights of speculation as to what we are, where we go, and the meaning of all things. To read Sir Thomas Browne again is always to be filled with astonishment, to remember the surprises, the despondencies, the unlimited curiosities of youth.

Speaking of symphonies, William Alwyn wrote Fifth Symphony: Hydriotaphia (1973) based “upon the rhythmical cadences” of Browne’s Urne Buriall, where “[e]ach section bears a quotation from [the book] and the music sets out to reflect these quotations though retaining its symphonic character throughout.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJlrVW_SR80

One possible cause of Browne’s writing in ‘Urn’ being stylistically so unlike any other 17th c. writer may be his having a hand in the medicine-cabinet. As a physician he was licensed to acquire and use opium, the only available pain-killer of the day. Opiate imagery/allusions occur in ‘Urn’ as quoted in your post.The 1650’s decade was also a time of deep melancholia for Royalist supporters, and it’s a curious coincidence that Browne was ‘re-discovered’ and raved over by Coleridge and De Quincey. Peter Green in 1959 (Writers and their work series Longmans no.108) was the first to suggest this, not I!

This is fascinating Kevin. He must have been fairly healthy to live seventy-five years.

I think reducing Browne’s style to opium addiction is a huge mistake. Or even saying, well, he couldn’t have written like that without opium. Right. And van Gogh couldn’t have painted like that without absinthe. And what was Milton on? Why is it so hard to believe he simply expressed himself uniquely? I have always failed to understand how we EXPECT phyiscal traits to be passed along through genes, we have no difficulty believing there’s a guy or a gal out there who is stronger, faster, more agile almost than seems humanly possible, but when it comes to creative genius, we act as though genes aren’t involved, and there’s a Houdini loophole somewhere–and it’s usually a drug.

That said, Samuel R. Delany has been raving about URNE-BURIALL for years and much to my shame I must admit I have never read more than fragments. I have no choice now but to go and buy a copy. I do find it a little ironic that Sebald, the master of the plain, who seemed dissatisfied if there was anything memorable about the language he used, wrote the intro to the master of the “Ornate Style.”

Well, we don’t know what was up with opium.

I don’t view Sebald as a master of the plain. Some of his sentences roll on in the ornate style.

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/26/books/chapters/28-1st-sebald.html